Read this story in Nepali- भारतका गुम्बामा बालक ओसारपसार : बालअधिकारको हनन्

Read our first part here: Passage to India: How Nepali Children Are Smuggled to Monasteries Across the Border to the South

***

Nearly seven years ago, in May 2019, 18 children, including Rajkumar Thing from Marin, Sindhuli, were taken to India through the Malangwa border crossing in Sarlahi.

Most of the children, including Rajkumar, who were taken to study in Indian monasteries, have returned home. However, there is no record anywhere of him going to and returning from the monastery in India for studies. Despite the ongoing practice of trafficking children from rural Nepal to monasteries in India under the pretext of teaching Buddhist education and making them lamas, such cases are rarely reported.

Most of the children, including Rajkumar, who were taken to study in Indian monasteries, have returned home. However, there is no record anywhere of him going to and returning from the monastery in India for studies. Despite the ongoing practice of trafficking children from rural Nepal to monasteries in India under the pretext of teaching Buddhist education and making them lamas, such cases are rarely reported.

Even now, children are being taken from Nepal to monasteries in India. However, there is no data on when this practice started and how many Nepali children are currently in Indian monasteries.

In the fiscal year 2021/22, Nepal Police registered 119 cases related to trafficking and transportation. In the fiscal year 2022/23, this number decreased to 75. Among these cases, those involving the trafficking of children to monasteries are few.

On December 7, 2021, Santabir Lama from Devchuli Municipality-17, Nawalparasi, who was charged by Nepal Police with human trafficking and transportation offenses, stated in his testimony that he had taken 70-80 children to monasteries in India over three years. His statement, that he used to take Nepali children to a monastery in Karnataka, India for studies, suggests that child trafficking occurs every year.

Furthermore, during the investigation of Santabir's case, the Kadampa Buddhist Foundation in Nepal, in a letter to the Human Trafficking Bureau at the Police Headquarters dated November 30, 2021, mentioned that someone from the Jyobo Kadampa Monastery went to Sar Gaden Monastery in Karnataka, India, for higher education around 1997. This clearly indicates that children have been taken from Nepal to monasteries in India for studies for a long time.

Despite this long-standing cross-border trafficking of children, not only is there a lack of proper legal provisions to prevent it, but even the existing laws are not being implemented. To the extent that the court itself has ruled that taking children to India for educational purposes does not constitute human trafficking or transportation.

On May 26, 2022, a similar verdict by Judge Uddhav Prasad Bhattarai of the Kathmandu District Court acquitted Santabir from Devchuli. This is despite Santabir admitting to taking children to monasteries in India for education, both in the past and at the time of his arrest.

According to the written statement given by Ramila Lama, a resident of Jorpati, Kathmandu, in this case, Santabir had even assured Ramila's brother-in-law, saying, "I will send you to India to study to be a lama. There's no future in studying to be a lama in Nepal. If you study to be a lama in India, you will become a great lama, even a teacher of lamas, and you can earn a lot of money."

The police, making the children Santabir was trying to take to India the plaintiffs, filed a case in court. One of the plaintiffs, a child whose name was changed to 26 Babarmahal (D1) by the police, stated that Santabir had met with his parents and said, "In Karnataka, you can acquire knowledge of Buddhist religion and become a great person and even a teaching master. Once you become a lama, you earn a lot of offerings. I have taken more than 70 people so far," and showed various inducements.

If children, or their parents or guardians, are transported through fear, intimidation, threats, use of force, false promises, or enticement, if someone receives payment for the transportation, or if the children who reach the monastery are unable to study and end up in child labor or slavery, leading to an exploitative life, it can be considered a form of trafficking.

However, the court did not consider these statements as evidence of inducement and acquitted Santabir.

Even though Santabir stated that he had been taking children to India for three years and was arrested in Sindhuli while going to get documents this time, the court did not examine the documents of the children he had taken to India previously.

Despite Santabir not having the necessary documents to take the children for education, the court relied on his verbal statement that he was taking them for education and delivered the verdict. Meanwhile, the Children's Act, 2075 considers crossing the border with children without documents to be illegal.

Article 3 of the Palermo Protocol includes such transfer of children within the definition of trafficking. Despite the sensitive nature of transporting children across borders without documents, proving the case becomes challenging due to insufficient evidence and unclear laws, according to Sandesh Shrestha, Joint Attorney at the Kathmandu District Attorney's Office.

Rule 15 (c) of the Children's Regulations 2078 ensures the preservation of children's religion, culture, language, identity, community, and family proximity. Tarak Dhital, the then Executive Director of the Central Child Welfare Committee, states that taking children to India under the guise of studying in religious schools without providing correct and clear information to the family is a crime.

Sub-section 1 of Section 6 of the Children's Act, 2075 states that no child should be separated from their parents against their will. Milan Dharel, former director of the Child Rights Council and a child rights activist, says that the issue of taking children abroad without documents, under the pretext of education or any other reason, is sensitive, and therefore, it is necessary to formulate regulations immediately to govern it. According to him, the government has not recognized the act of taking children from Nepal to monasteries in India and transporting children studying in monasteries in Nepal to monasteries in India as a crime.

Kapil Aryal, Associate Professor at Kathmandu School of Law and a child rights activist, states that taking Nepali children to Indian monasteries for any reason without the approval of the local level and the National Child Rights Council can be considered a form of human trafficking if it involves transporting children by instilling fear, intimidation, threats, use of force, false promises, or enticement to the children, their parents, or guardians.

According to the Children's Act, 2075, children have the right to be protected from any work that harms them or hinders their education or harms their health, physical, mental, moral, and social development. However, those who take children to India against this right do not provide information about the education that will be provided to the children and adolescents. As a result, the children are deprived of quality education.

Sub-section 2 of Section 15 of the Act states that every child shall have the right to receive education up to the basic level compulsorily and free of charge, and education up to the secondary level free of charge, in a child-friendly environment, as per prevailing law. However, children are being trafficked across borders for studies using illegal means without completing the necessary procedures. As a result, children are deprived of receiving quality education while living under the care of their parents.

Sub-section 2 (e) of Section 66 considers it an offense to make someone beg for alms, or to make them wear the guise of a sanyasi, monk, fakir, or any other disguise, except for traditional customs or religious or cultural programs.

Advocate Somraj Luitel says that the law does not clearly define what kind of religious and cultural programs children can be used for. "Who takes the guarantee that the children sent in this way will be safe? They can also be at risk of trafficking," Luitel says, "The government should bring clear laws to address this issue."

According to Advocate Luitel, the trafficking of children to monasteries in India involves a bit of education, a bit of religion, and a bit of trafficking and transportation, and due to the lack of a responsible body, illegal transportation is occurring. He says that stakeholders are also confused.

Buddhist writer and scholar Basant Maharjan states that there are no government policies or regulations for religious schools. He says, "But this is not just a religious matter. The state can and should monitor religious and cultural schools as well."

Advocate Luitel says that the law should specify the body that grants approval if someone needs to be taken for religious and cultural education. "The Children's Act and Regulations also do not provide a clear explanation, so the Act needs to be amended," he says.

According to General Comment Article 13 of the United Nations (UN), education varies according to the context of the country, and this includes religious and traditional education. Therefore, traditional and religious schools are not the problem. However, Milan Dharel, Director of the Child Rights Council and a child rights activist, says that the government should regulate them. According to Dharel, the environment of traditional and religious residential schools, including monasteries, should be child-friendly and safe.

Whose responsibility is it to protect children?

The Palermo Protocol is a protocol to the United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime aimed at combating transnational organized crime. Nepal is a party to both the protocol and the convention on combating human trafficking and transportation.

Section 9 of the Treaty Act, 2047, explains that the provisions made by conventions ratified by the Parliament of Nepal and to which Nepal is a party are equivalent to Nepali law. In this sense, it is the government's responsibility to implement the definitions made by the Palermo Protocol.

According to this definition, if children, or their parents or guardians, are transported through fear, intimidation, threats, use of force, false promises, or enticement, if someone receives payment for the transportation, or if the children who reach the monastery are unable to study and end up in child labor or slavery, leading to an exploitative life, it can be considered a form of trafficking. Therefore, Professor and child rights activist Kapil Aryal states that taking Nepali children to Indian monasteries is a form of trafficking.

After incidents of sexual abuse came to light, the Ministry of Home Affairs made a decision on December 13, 2021, regarding the transfer of children from one place to another, in the context of taking children under the promise of providing educational opportunities and care in the name of social, religious, or other organizations and sending them abroad or using them as domestic workers.

Decision No. 2(a) states that if it is necessary to take someone from Nepal to a foreign country for educational purposes, an NOC letter from the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology, or, in cases where an NOC letter is not issued, a letter of approval from the relevant local administration is required. However, in the cases we encountered, no child was found to have been taken to India after completing these procedures.

Section 8 of Chapter 3 of the Education Act, 2028 (amended 2074), Rule 9 of the Education Regulations, 2059 (amended 2077), and the National Education Policy, 2076, provide for the approval of foreign educational institutions and affiliated educational institutions, and for operating educational programs or opening schools in affiliation with foreign educational institutions. However, the regulations do not seem to address the provisions for children and adolescents going to India and other countries for traditional and religious cultural education. Meanwhile, individuals over 18 years of age are given a No Objection Certificate (NOC) for foreign studies.

Ram Prasad Sharma, Head of the School Education Branch at the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology, informed that there are no separate regulations for children under 18 years of age who need to go abroad for residential studies. He admits that the ministry has not been able to focus on making laws to address this.

Chapter 3(b) of the Traditional Educational Institutions (Operation and Management) Standards, 2079, states that the operation and management of institutions providing traditional education should be made timely and the educational programs being run by such institutions should be brought into the mainstream of the education system. It states that these schools should come under the purview of the Ministry of Education's regulations. However, this is not seen in practice.

According to the Formal and Alternative Education Branch of the Center for Education and Human Resource Development, monasteries provide education up to grade 12. The branch's data shows only 67 students in these monasteries. However, according to the Gumba Development Committee's data, there are 3,150 students in the monasteries.

According to Dharel, the then Executive Director of the Child Rights Council and a child rights activist, educational institutions that take children for residential studies outside of Nepal must be registered, records of the person taking them, the children, and the parents must be kept, and a report including the curriculum, environment, and condition of the children there must be sent to the ministry. The Ministry of Education should make laws covering aspects such as whether parents are capable or willing to educate them, or if they are going without alternatives.

Silence of the Gumba Development Committee

The Gumba Development Committee was formed to protect and promote Buddhist monasteries and viharas, and to facilitate Buddhist studies and development. However, the committee appears to have remained silent even as children are being trafficked without documents to India and other countries to become monks and study in monasteries.

As this issue is related to children, it is more closely connected to the Ministry of Women, Children and Senior Citizens and the Ministry of Education. It seems necessary for the ministry to clearly explain this issue when formulating policies to address it. Moreover, Milan Dharel, the former Executive Director of the Child Rights Council and a child rights activist, has experienced failure in trying to initiate policy through inter-ministerial meetings regarding the issue of taking children to monasteries in India, even when it was to be included in the Act and Regulations.

He says that even when they prepared and sent a draft to be included in the Regulations of 2078, the Ministry of Women, Children and Senior Citizens did not include it.

Ram Bahadur Chand, Information Officer at the Child Rights Council, shares a similar view. Even when the Child Welfare Committee was active, inter-ministerial discussions were held to formulate separate regulations to address this issue. He stated that they were unsuccessful in making regulations at that time as well. Chand's experience is that subsequent attempts to include it in the Children's Act also failed. After it was not included in the regulations, the Ministry of Home Affairs issued a circular. He speculates that the existence of the circular might be the reason for the lack of interest in making regulations.

Chand, the spokesperson for the council, confirms that the government considers taking children abroad for residential studies in traditional, religious, cultural, and other subjects as normal.

To manage this, local levels should also create separate laws. The lack of clear policies and regulations may be why those taking children are choosing easier routes. There should be a clear explanation of which body issues the documents. There should be a clear explanation of who grants permission. There is no clear explanation of this. A separate procedure is needed for this. The law mentions that local levels will recommend, but it does not clearly state who grants permission. Dharel emphasizes that the council should be empowered for this.

After getting imprisoned for 7 months, I stopped taking children to monasteries

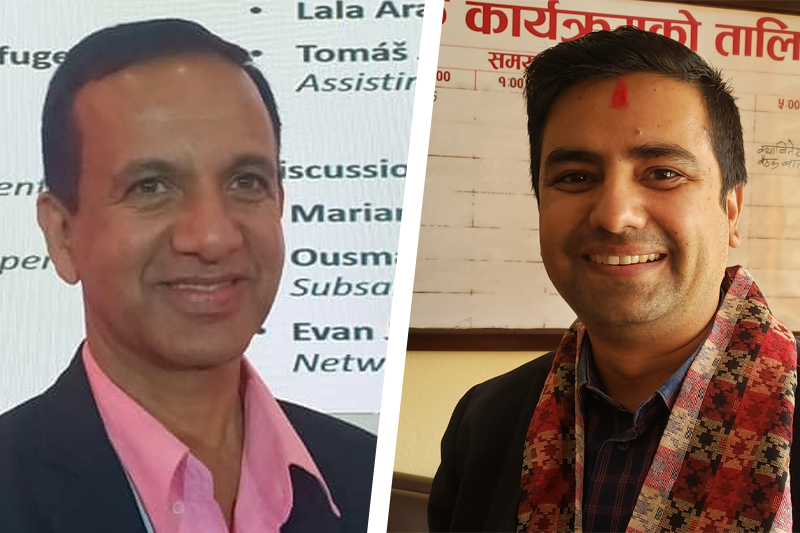

Santabir Lama

I was arrested with two children and jailed when I went to the ward office of Sunkoshi Rural Municipality-2 in Sindhuli to get a recommendation to take children to a monastery in India. I had kept five children at Jyobo Kadampa Gumba, also known as Jhugo Kadampa Gumba in Aarubari, to take them to study at Syar Gaden Monastery in Karnataka, India.

When I came to Nepal on vacation from Syar Gaden Monastery in Karnataka, India, I used to take children with their parents' permission. I used to take them only after getting a recommendation from the ward, and I know that it's only allowed to take them if a recommendation is given. That's why I went to Sindhuli to get a recommendation to take them.

I had lent 27,000 rupees to one of the children I was taking because he didn't have a mobile phone. His friends were also with him, and I had gathered them to take them to the monastery as well. If the monastery doesn't provide money to take them, I have to spend my own money. I haven't benefited anything from it.

After being arrested while going to Sindhuli for the recommendation and spending 7 months in jail, I have stopped the work of trafficking children to monasteries.

In my free time now, I teach Tibetan language, tell fortunes, visit local monasteries, and do ritual work at Jyobo Kadampa Gumba in Aarubari.

Children are brought to that monastery in India not only from Nepal but also from various cities in India itself, as well as from China, Tibet, and Mongolia. Currently, there are about 300 monks in that monastery. Some have come from Europe to become monks. They are in their 30s and 40s.

One can only come home after studying there for 4-5 years. When they come home for vacation, children who are fatherless, motherless, or both parents are deceased and living with relatives are particularly taken. Some children are taken at the request of their parents.

I was also taken to the monastery to study when I was 15 years old. After studying for three years at a monastery in Thali, Nepal, I and my friends were taken by teachers who came from India.

Before coming to Thali, I studied up to grade 3 at a monastery in Daunne, Nawalparasi. From there, I went home and later came to Kathmandu. My father was also a lama, so he sent me to Kathmandu to study. After going to the monastery in India, studying for 18 years and getting a degree, I returned to Nepal and started teaching part-time at monasteries here.

(Based on an interview with Santabir)

If you want to republish this material, please do so in accordance with our republication policy. The republishing guidelines are here.